Public Lands, Public Ownership

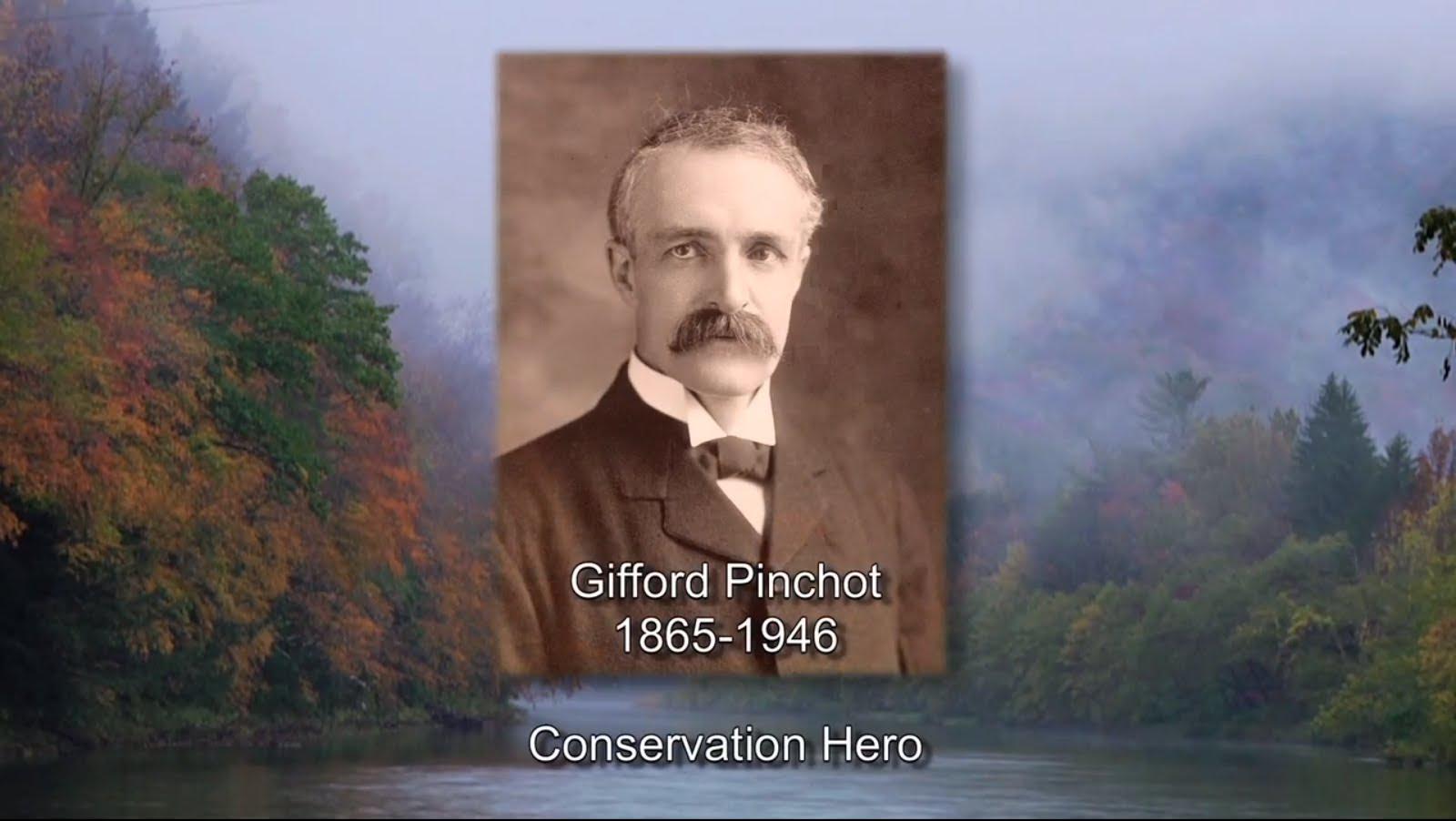

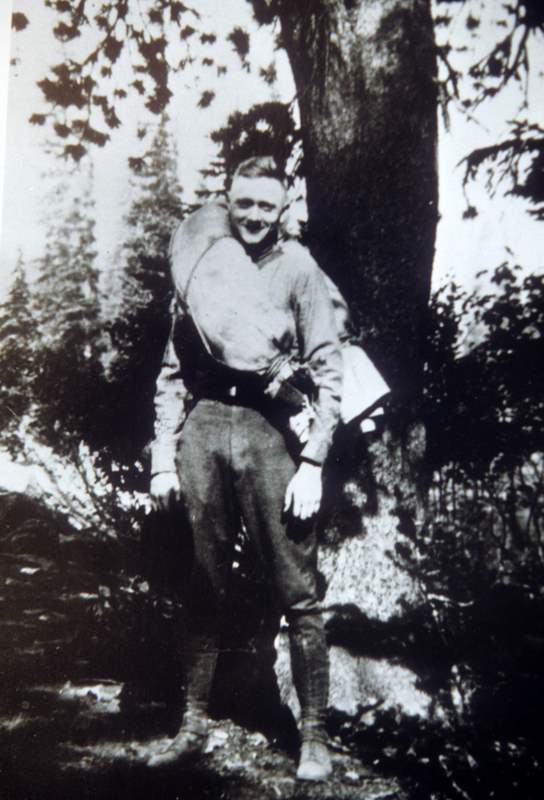

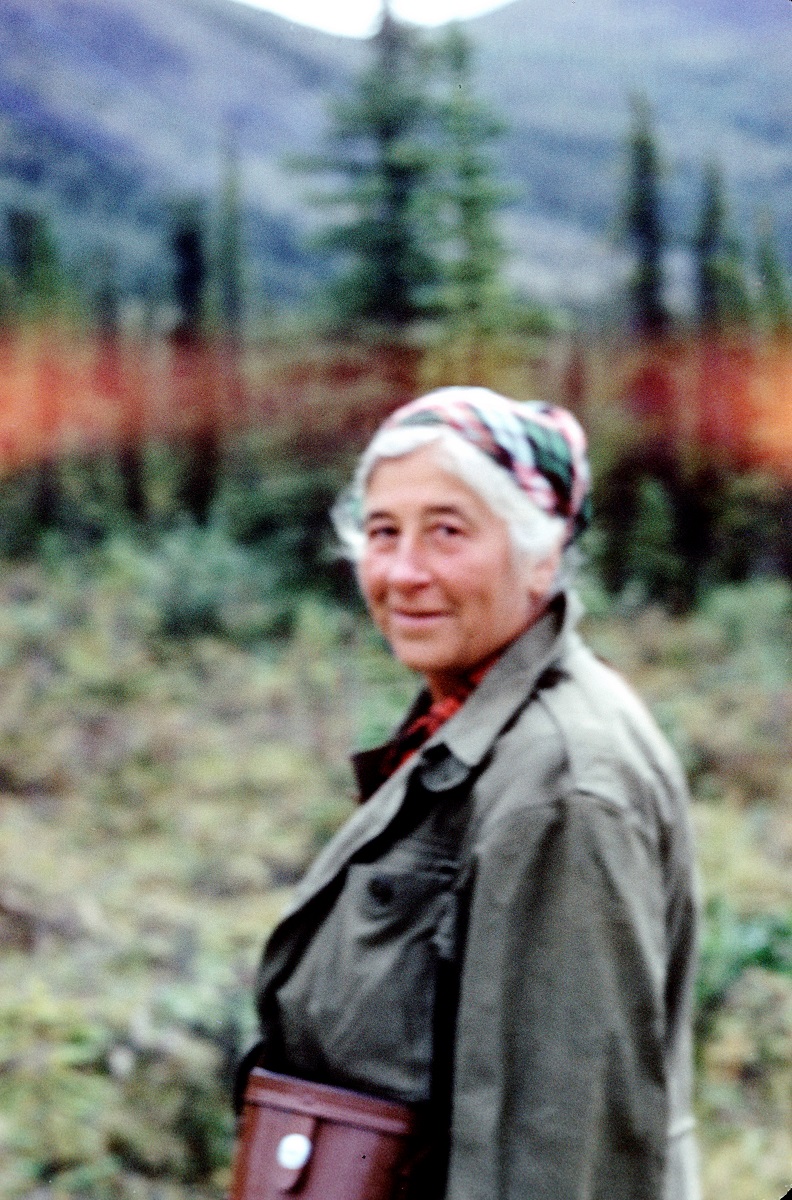

Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas used his stature and talents to present the case for conservation. He passionately and eloquently engaged the public and pressed them to defend our national heritage against the disfigurement of natural beauty, pollution of our air and water, and the decimation of wildlife.

Stewardship of the natural world was more than a pleasing diversion for Justice Douglas. He considered wild places a necessary ingredient for a healthy democracy and the inheritance for future generations.

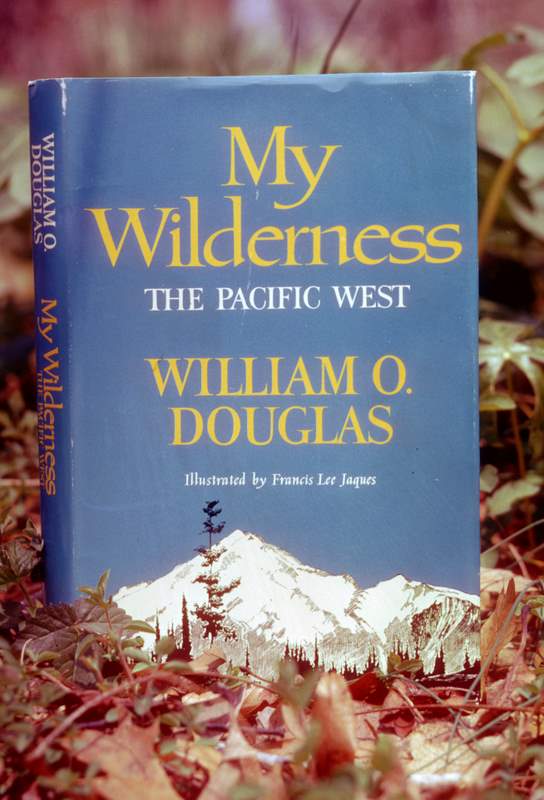

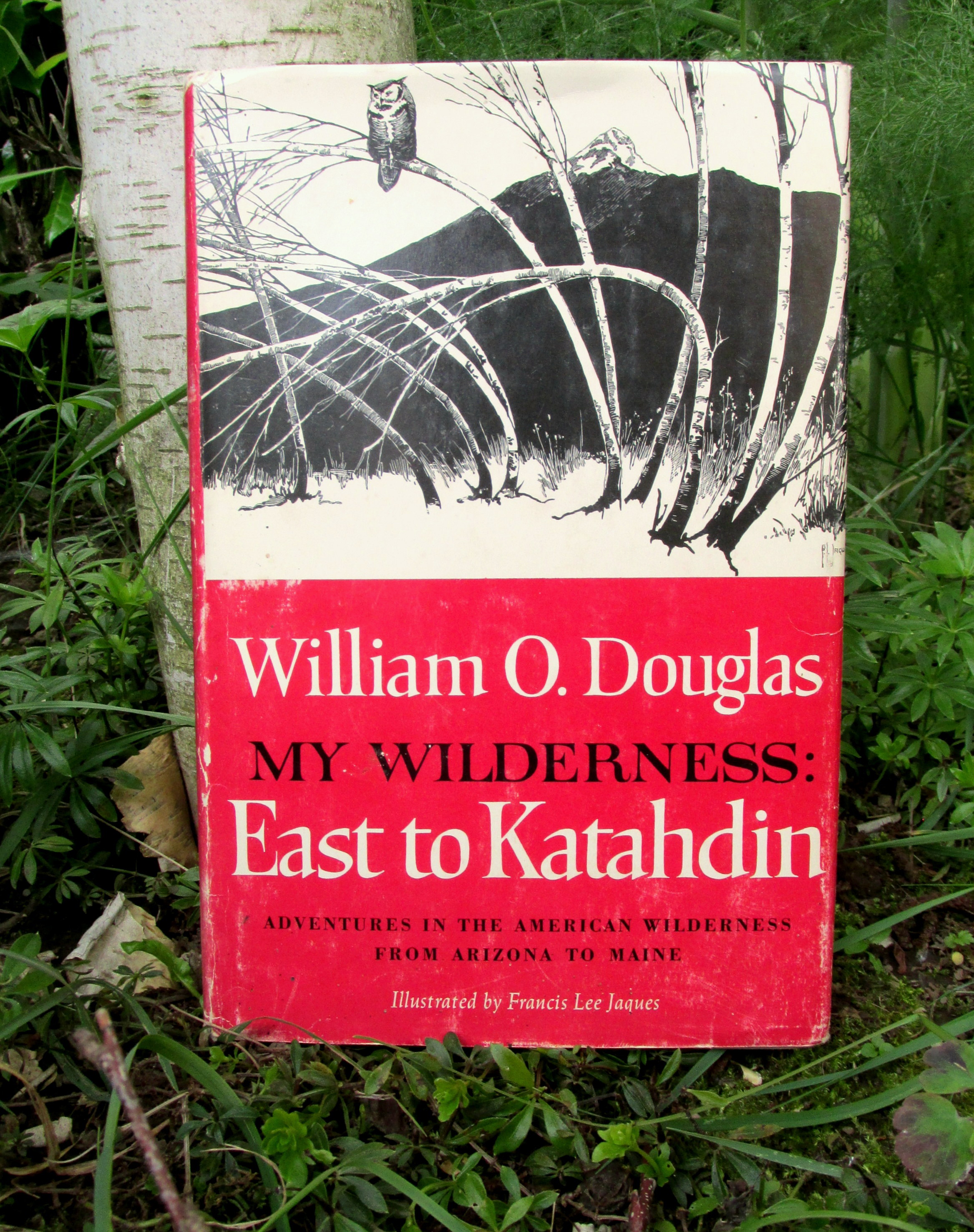

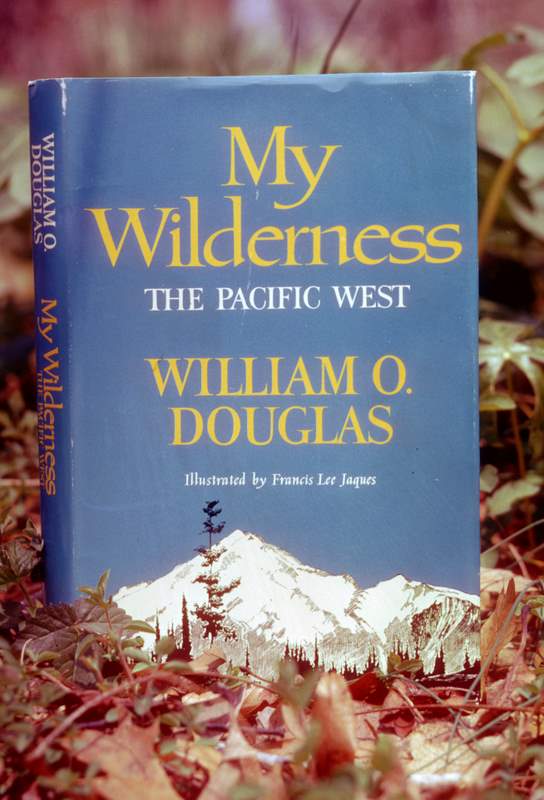

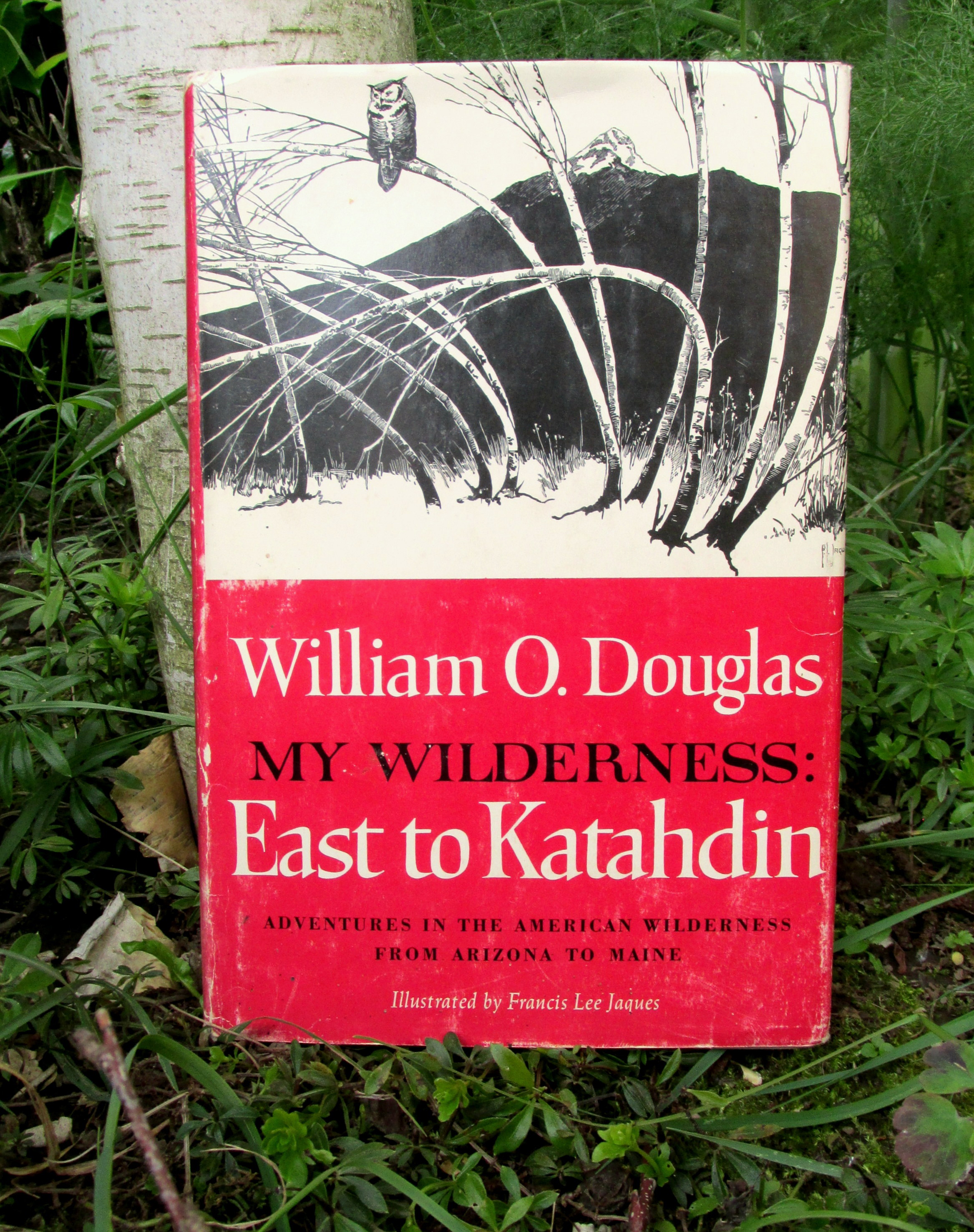

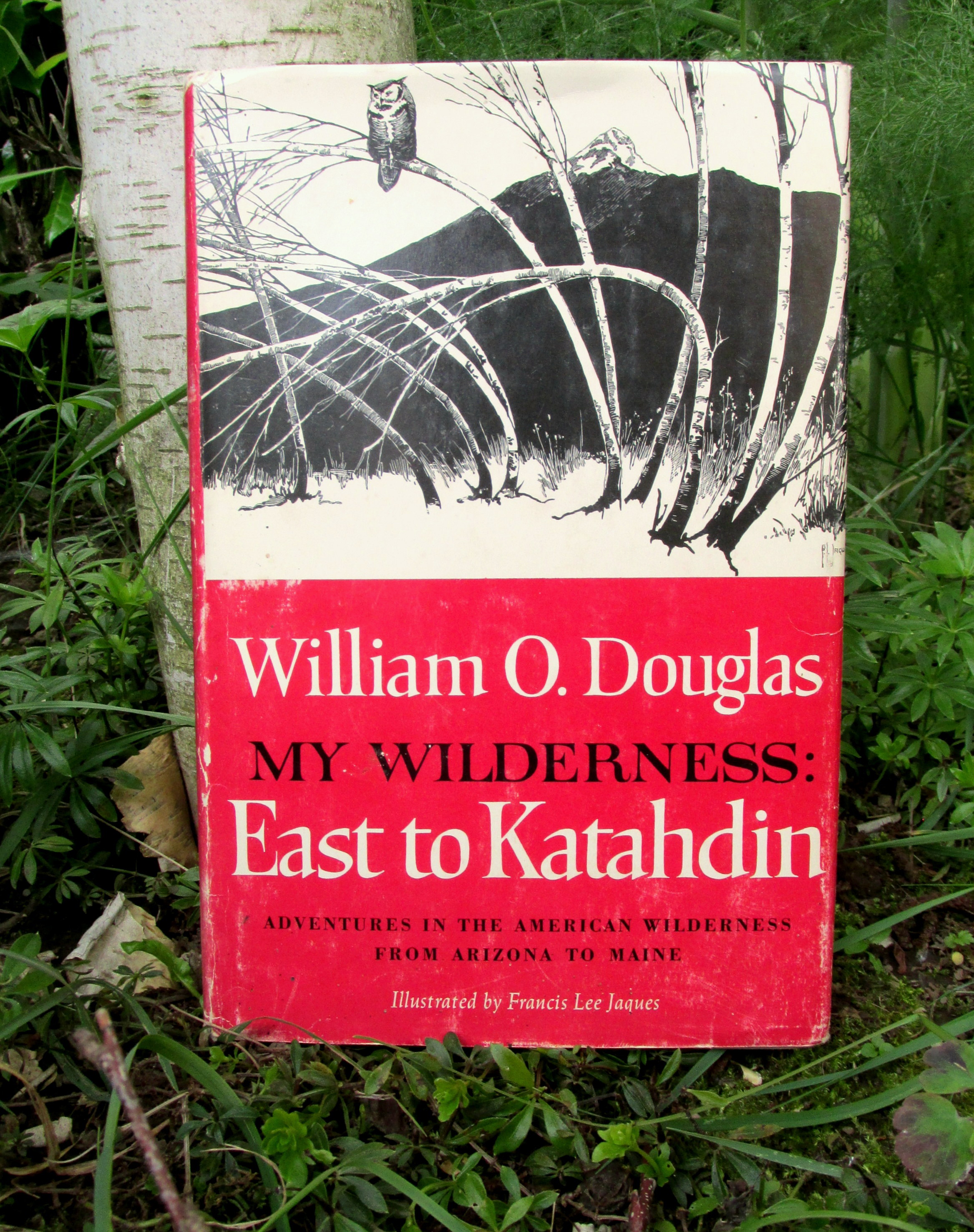

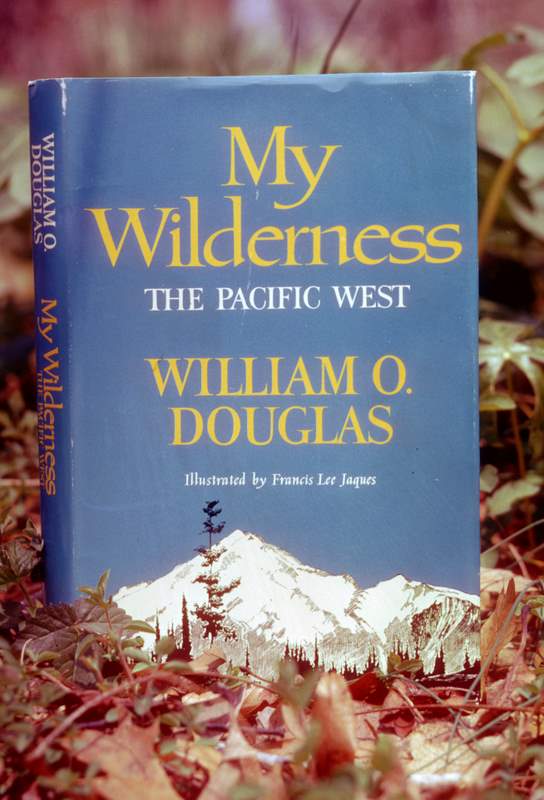

William O. Douglas authored more than 40 books, many of them best sellers including My Wilderness: The Pacific West, My Wilderness: East to Katahdin and The Wilderness Bill of Rights. Excerpts from two of these works are featured below.

Justice Douglas stated in his autobiography:

I hope it may help them [the American people] see in perspective of the whole world the great and glorious tradition of liberty and freedom enshrined in our Constitution and Bill of Rights. I hope that before it is too late they will develop a reverence for our rich soils, pure waters, rolling grass country, high mountains, and mysterious estuaries. I hope that they will put their arms around this part of the wondrous planet, love it, care for it, and treat it as they would a precious and delicate child. (Go East Young Man, 1974)

Adam M. Sowards is a professor of history at the University of Idaho and the author of The Environmental Justice: William O. Douglas and American Conservation

How are public lands in America threatened?

It is a fundamental American concept that our public lands belong to everyone. Hundreds of millions of acres of national forests, rangelands, wildlife refuges, state and national parks, wilderness areas and historic sites are publicly owned, and managed by agencies, mostly federal. It is a misnomer to say they are federally owned.

Justice Douglas called for coordination of local and national conservationists in Committees of Correspondence, as patriots had done during the American Revolution to protect the “inheritance of all the people…a dividend of national citizenship.”

The locations described in this lesson represent the gamut of these lands from Alaska to Arizona to Maine. These examples illustrate the spectrum of geography and management involved in public lands.

These places are vulnerable and imperiled in many ways; wildfires, pollution, overuse and irresponsible resource practices to name a few. In addition to Justice Douglas’ narratives describing these lands, this website addresses the threat to public ownership and, access to them and the role policy making plays in these issues .

NOT to boast, but that image is me enjoying a pristine alpine lake I own in the California Sierras. It’s property so valuable that Bill Gates could never buy it. Yet it’s mine.

It’s part of America’s extraordinary, but now threatened, heritage of public lands.

Bird Creek Meadows: Now and Then

History & Jurisdiction

Mount Adams is a 230-square-mile stratovolcano mountain located in south-central Washington state, which lies mostly within the Gifford Pinchot National Forest and Yakama Indian reservation.

With its summit at 12,276 feet, Mount Adams is the second highest peak in Washington State and the third highest peak in the Cascades Range.

Mount Adams climbing routes and summit are within Mount Adams Wilderness and are protected and managed to preserve its natural condition. The 47,000-acre Mount Adams Wilderness was designated by Congress in 1964 as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Mount Adams is mantled by 12 glaciers, most of which are fed radially from its summit icecap. The total glacier area of the 12 glaciers has decreased by 49% from 1904 to 2006. Similar trends have been documented on all Cascade Range peaks.

Gifford Pinchot National Forest management is based on its Land and Resource Management Plan which was modified in February 1995 to reflect the April 1994 Northwest Forest Plan.

In 1972 President Nixon issued Executive Order 11670, which authorized the return of a 21,000-acre portion of Mount Adams, including the summit, to the Yakama Nation. The Yakama Nation Mount Adams Recreation Area is open to the public during summer seasons.

Darvel Lloyd and Darryl Lloyd of Friends of Mount Adams contributed to this section.

William O. Douglas on Mount Adams

When I was a boy I could see Mount Adams from our front porch in Yakima. It is snow-capped the year round and shows various moods depending on the weather. On clear days of Summer it is resplendent in the bright rays of the morning. Before a storm moves in from the west, the mountain seems to tower in dark rage. The fires that come when the humidity drops and forests dry out sometimes cast a pall of smoke over the land. Then Mount Adams has softer lines and is distant and indistinct, a mountain of mystery. If the sun sets clear, there is a moment before the mountain is swallowed up by darkness when it is brightly luminous, incandescent, a startling ball of cold light. When the moon rises, the distant snow fields dimly lit reflect a golden glow. Then the mountain seems so far, so remote, as to belong in another world.

I had not seen Bird Creek Meadows for over thirty years. I left Glenwood by jeep, planning to park at the road’s end and hike in, as I used to do. As the jeep climbed on and on, I discovered to my dismay that the good dirt road went all the way. When arrived, I counted twenty-seven cars ahead of me. My heart sank. An alpine meadow that I used to reach only after days of hiking was now accessible to everyone without effort. It had been desecrated by the automobile.

In the days that followed, I was greatly depressed by this transformation of Bird Creek Meadows. Potbellied men, smoking black cigars, who never could climb a hundred feet, were now in the sacred precincts of a great mountain. Part of the charm of Bird Creek Meadows had been their remoteness and the struggle to reach them. Their romantic nature had been diluted. The mountain was still as magnificent as ever; the sky as blue; the fireweed as brilliant. But the meadows were no longer a sanctuary.*

Man must be able to escape civilization if he is to survive. Some of his greatest needs are for refuges and retreats where he can recapture for a day or a week the primitive conditions of life. The loggers and road builders look at every lovely ridge or basin for quick profits. They take heavily from the forests, sometimes destroying everything. There are others who take nothing from the forest except inspiration and high purpose. Their lives and character are indeed shaped by it.

The logistics of abundance call for mass production. This means the ascendency of the machine. The risk of man’s becoming subservient to it are great. The struggle of our time is to maintain an economy of plenty and yet keep man’s freedom intact. Roadless areas are one pledge to freedom. With them intact, man need not become an automaton. There he can escape the machine and become once more a vital individual. If these inner sanctuaries are preserved, every person will have a better chance to maintain his freedom by allowing his idiosyncrasies to flower under the influence of the wonders of the wilderness.

These were my thoughts that night as I sat on my lawn watching the last glow of the sun leave the high snow fields of Mount Adams.

(My Wilderness: The Pacific West, 1960.)

*NOTE: The last stretch of road to Bird Creek Meadows has been decommissioned and it is a three-quarters of a mile hike up into the Meadows today.

Darryl Lloyd and his family were neighbors with Justice Douglas and his family in Glenwood, Washington in the 1950s. He is a founding member of the Friends of Mount Adams.

Impending Threats to Public Ownership

In Washington state, three bills have been introduced or are pending in 2016. In 2015, three bills were introduced in the state legislature and two are still under consideration. Most of these bills are study bills, meaning the state would create a "task force" to study how to take over public lands. One current bill is the most aggressive yet, demanding the wholesale transfer of all public lands in the state to the state government to manage. Read more at: www.protectourpublicland.org/washington.

A Yakama Nation Tribal Resolution in 1971 maintains wilderness use for the public. Although unlikely, the Yakama Nation by tribal council may elect to limit access to parts of Mount Adams that were previously under US Forest Service management.

The Wilderness areas on Mount Adams are protected by the Wilderness Act.

Author and CNN Presidential Historian Douglas Brinkley on William O. Douglas' connection to the natural world.

History & Jurisdiction

The 2,065-acre Baboquivari Peak Wilderness is 50 miles southwest of Tucson, Arizona in Pima County.

The wilderness includes a small, spectacular portion of the east side of the Baboquivari Range. The sharp rise of Baboquivari Peak dominates the wilderness area. Vegetation varies from saguaro, paloverde and chaparral communities to oak, walnut and pinyon at the higher elevations.

On Arizona's smallest designated Wilderness, Baboquivari Peak rises sharply to dominate the scenic desert terrain of the east side of the Baboquivari Range, near the Mexican border. The Tohono O'odham Nation is situated on the western side of the range.. Baboquivari, near the southern end of the area, rates as the only major peak in the state requiring technical climbing ability to reach the summit, a popular attraction for rock climbers.

The United States Congress designated the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness in 1990. All of this wilderness is located in Arizona and is managed by the Bureau of Land Management

William O. Douglas on Baboquivari Peak

Baboquvari is a granite shaft 7,730 feet high that watches over the United States-Mexican border…It’s a tiptop point of a range some thirty miles long. While the range looks barren and bleak from a distance, Baboquivari has grandeur and nobility.

The peak has many moods. Mornings when the skies are clear it has a dazzling splendor. By noon the desert dust riding high in the heavens often casts a haze about it. Then its sharp lines are gone and it becomes softer and more remote-a bit out of focus. On a clear day it has a bluish tinge. By midafternoon, when shadows lengthen, Baboquivari seems to tower even higher in the sky. It then turns a dark purple.

The south and west sides of the mountain are fringed with cliffs. They are 200 to 1200 feet high, dropping as straight as the canyon walls of Wall Street . . . . Some are like spires of a cathedral. There are lateral ridges, a half mile or so long. Rough points of rock curl out from the main ridge to form huge promontories. The main ridge bends in the shape of a fishhook. The result is a series of pockets, alcoves, basins, hemmed by gargantuan cliffs. Twenty-five hundred feet deep in one canyon is a great stand of saguaro.

This kind of cacti stands thirty to fifty feet high. Until it is about seventy-five years old, the saguaro is a single stalk, twelve to eighteen inches in diameter. Then it grows branches—arms that are round and chunky like the main stem itself, arms that point gracefully to the sky or that droop sadly. The trees, with their arms thrown skyward, look like dancers frozen in some weird pantomime. Saguaro, in Indian means friend, and friend it was to those people. It’s beautiful white flowers (that are nocturnal and the fragrance of a ripe melon) produce a figlike fruit food to eat. Its seeds make up into a butter. Its wood furnishes shelter and fuel.

Baboquvari’s creation was perhaps fifty million years ago. Once a great volcano probably stood here. Then molten rock welled up in the core of the volcano and hardened into a solid plug. The sides of the volcano weathered and wore off, leaving a pillar of rock. This was millions of years before man appeared on the scene, with his plots and his schemes.

Once I started down from the top at five o’clock—two hours from dark. Black clouds were rising from the Gulf of California. The sun sent streamers of color through them. First there was gold; then the gold faded, and in quick succession came red, gray and purple. The clouds changed so fast in color, and so subtly, that one could imagine giant spotlights being played on the heavens. This was a sunset that only Arizona can produce. I caught myself stopping on the trail to watch it, letting precious moments of the remaining daylight pass.

(My Wilderness: East to Katahdin, 1961)

Impending Threats to Public Ownership

A law forming a committee to study the transfer of public lands to the state was signed by Arizona's governor . Additionally, other related bills have made it out of committee, including one to band together with Utah in a state compact to pursue this idea. In 2016, the state introduced three new bills, including a new approach to land takeovers, called "Catastrophic Public Nuisance" bills. These bills, crafted by the private interest American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), would enable "executives," including state governors and even county sheriffs, to seize public land if they deem necessary because of any number of conditions, including insects, air quality, or a need for vegetation for livestock. Read more at: www.protectourpublicland.org/arizona

Mary Christina Wood is the Philip H. Knight Professor of Law and Faculty Director of the University of Oregon Environmental and Natural Resources Law Program and author of The Public Trust Doctrine in Environmental Decision Making. A passionate advocate, her writing on the use of the Public Trust doctrine to compel government action on global stewardship is being used to in cases brought on behalf of the children throughout the United States. Renowned journalist Bill Moyers hosted Wood as the last guest on the last episode of Moyers & Company.

History & Jurisdiction

The Wallowa Mountains lie within the 2.3 million acre Wallowa-Whitman National Forest.

Wallowa Lake is the signature geological feature of this rugged range, formed by moraines left over from the last ice age. The lake itself was carved out by periods of glaciations that started 3 million years ago and ended around 15,000 BC. Some moraines reach 900 feet in height and make for a dramatic backdrop, with the Wallowa Mountains—“the Oregon Alps”—ringing the south end of the lake. Wallowa Lake has served as a recreation destination since 1880.

The world’s largest caught kokanee salmon was pulled out of the Wallowa Lake, a colossal 27 3/4 inches that weighed in at 9.67 pounds.

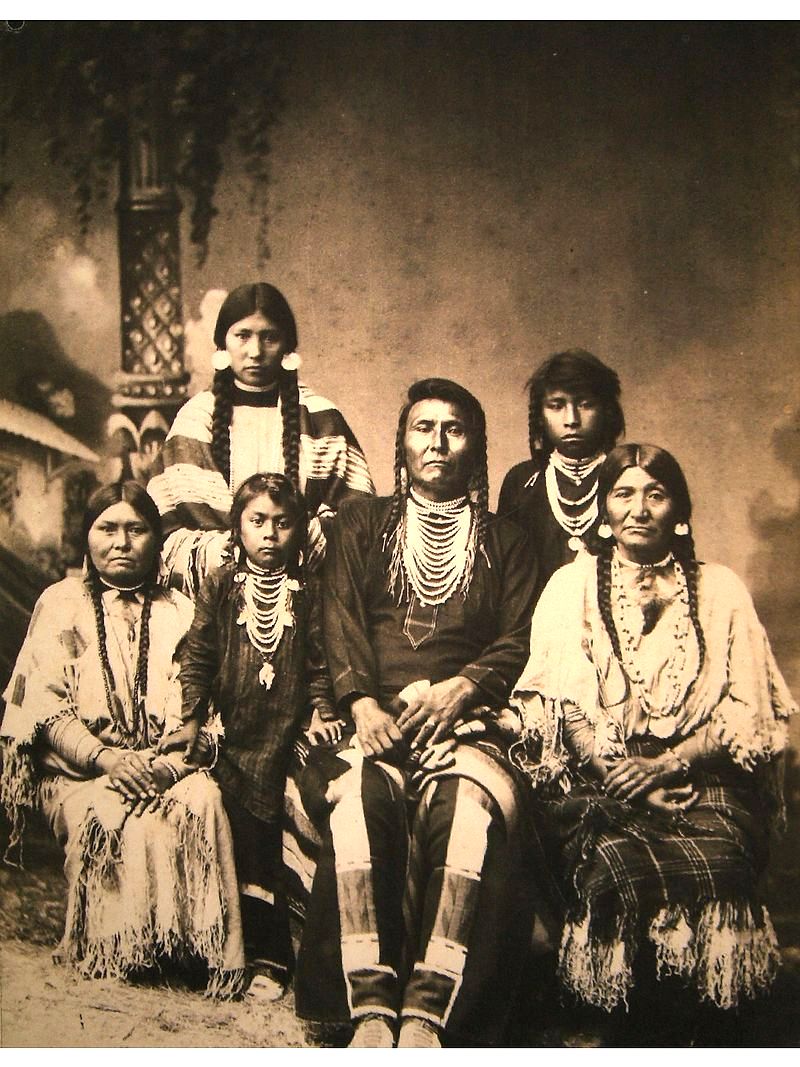

The Eagle Cap Wilderness, at 361,446 acres (556 sq. miles) is Oregon's largest wilderness area, was the summer home to the Joseph Band of the Nez Perce tribe. The first settlers moved into the Wallowa Valley in 1860.

Within these white salt-and-pepper granite mountains, you'll find approximately 534 miles of developed trails and over 50 lakes inside the boundaries of this wilderness area to explore, including Legore at an elevation of 8,880 feet—Oregon's highest.

William O. Douglas on The Wallowas

The Wallowas (which lies in Oregon at the corner where that state touches Washington and Idaho) are shaped like a huge wagon wheel. Eagle Cap being the hub and the Lostine and Minam canyons being the two of the spokes. The North Minam Meadows is the headwaters of the North Fork of the Minam River.

There are over a hundred lakes in the Wallowas.

Some, like New Deal, rest in treeless basins. Mud Lake is a tiny pocket on a steep slope. Cheval is a deep hole at the end of a great talus slope—large enough to accommodate only one party. Douglas is rimmed by granite spires, Bumble, Patsie and Tombstone are like ponds in friendly pastures. Green, Minam, and Crescent are rich with algae. Blue and Chimney show clayish bottoms and have a sterile look. Hobo has golden trout. Long-noted for rainbows —is a wide expanse that shows whitecaps on windy days. Swamp-filled with golden trout—lies in a large basin, rimmed by slopes that show countless rockslides and decorated by ancient and elegant whitebark pine.

But my favorite of all is Steamboat, out of which the North Fork of the Minam rises. It is rimmed by talus slopes and by granite walls highly polished by glaciers. Alpine fir has taken hold in many places. Whitebark pine and Englemanns’s spruce compete for second place. A meadow of ten or twenty acres fills one end of this basin. The lake occupies the rest, creating the impression that it rests in a large saucer that is about to spill over at one end. Polished-granite ledges run at a gentle slope into the sapphire-blue water, where eastern brook trout live. This is a fly fisherman’s paradise. High benches are ablaze with the tiny purple bush penstemon. The lake’s edge is gay with pinkish, waxy flowers of the pyrola. My map is not in the meadow but in a small cluster of conifers at the opposite end. An ice-cold stream hardly a foot wide runs on the edge of these trees. It has a white sandy bottom and is excellent refrigeration for food. One sits on top of the world at Steamboat Lake.

The nights are crisp; the dawn is fresh with dew. This is a world unto itself, untouched by civilization, unspoiled by man.

(My Wilderness: The Pacific West, 1960.)

Impending Threats to Public Ownership

A total of four bills in the state legislature demand federal land be transferred to Oregon. Unique amongst the western states pursuing this idea, one bill even goes so far as to demand National Park units be transferred as well. Read more at: www.protectourpublicland.org/oregon.

History & Jurisdiction

Mount Katahdin is the highest mountain in Maine at 5,270 feet . Named Katahdin by the Penobscot Indians, which means "The Greatest Mountain", Katahdin is the centerpiece of Baxter State Park. It is a steep, tall mountain formed from a granite intrusion weathered to the surface. It has inspired hikes, climbs, journal narratives, paintings, and a piano sonata. Katahdin is the northern terminus of the Appalachian Trail.

The ownership history of Baxter State Park is unique. Not really a “state” park, it was a gift to the people of Maine from a single philanthropist, Percival P. Baxter.

Baxter was governor of Maine during the years of 1921-1924. He enjoyed fishing and vacationing in the Maine woods throughout childhood and his affection for the land and wildlife were instrumental in his creation of a park. He began to fulfill his dream in 1930, with the purchase of almost 6,000 acres of land, including Katahdin. In 1931, Baxter formally donated the parcel to the State of Maine with the condition that it be kept forever wild.

Over the years, Governor Baxter purchased additional lands and pieced his Park together, transaction by transaction. He made his final purchase in 1962. Since then, additional purchases and land gifts have increased the Park's total size to 210,000 acres. About 75% of the Park is managed as a wildlife sanctuary.

In the northwest corner of the park, 30,000 acres were designated by Governor Baxter to be managed as the Scientific Forest Management Area and is currently a Forest Stewardship Certified showplace for sound forestry.

Several years prior to former governor Baxter’s death in 1969, Justice Douglas wrote this tribute:

"Percival P. Baxter is our foremost conservationist. He was a pioneer whose voice pleaded for wilderness values when exploitation was the theme of the day. Biologists, botanist, ecologist — he has helped educate two generations of Americans on the spiritual values of the outdoors, of free-flowing rivers, of alpine meadows, of cold pure springs."

About 25% of the Park is open to hunting and trapping with the exception that moose hunting is prohibited.

It is administered by a special authority and is independently funded. The primary responsibilities of the authority are to protect the wildlife, fauna and flora within the park for the enjoyment of present and future generations. A continuing effort to live up to this important resource-first and people-second requirement is the guiding philosophy of the park's management today.

Howard R Whitcomb of Friends of Baxter State Park contributed to this section.

William O. Douglas on Katahdin

There are hundreds of lakes to be seen from the top of Katahdin—a view which Thoreau compared to a thousand fragments of a broken mirror that had been scattered far and wide.

Years ago I used to go to this northland in June, when the salmon-fly hatch began. When I practiced law in New York City and later, when I was with the Roosevelt administration in Washington D.C., I arranged for news of the salmon-fly hatch to be wired me at once. Within twenty-four hours I would be casting a fly in Maine. That is when my love of Maine woods and waters began. I came to know a few of their secrets—and, better still, the men who walked the Maine woods and paddled the canoes.

The lakes of Maine are almost without number. I forget the names of all I fished. Sometimes I went far north, close to the Canadian border, in my search for salmon. But I always returned to Katahdin, and its restful marshlands where the mountain made man lift his eyes.

We must multiple the Baxter Parks a thousandfold is order to accommodate our burgeoning population. We must provide enough wilderness areas so that, no matter how dense our population, man—though apartment born—may attend the great school of outdoors, and come to know the joy of walking the woods, alone and unafraid.

Before long he will cease to enter our wild precincts as a predator. He will come with a reverence. Then he will walk the woods quietly and humbly. He will come to know that man needs a Bill of Rights for his wilderness—a Bill of Rights that includes the privilege of drinking for a pure, cold—water spring. If that is to happen, the places where the goldthread, monkey flower, spring beauty, or starflower flourish in sphagnum moss must be made as sacred as any of our other shrines.

(My Wilderness: East to Katahdin, 1961)

Douglas Brinkley talks about Justice Douglas and his consciousness raising efforts in Washington DC

Impending Threats to Public Ownership

The lands that compose Mount Katahdin have permanent protection. This was a condition of this gift to the public by Governor Baxter in 1931. The deed of trust stated "…said premises shall forever be used for public park and recreational purposes, shall forever be left in the natural wild state, shall forever be kept as a sanctuary for wild beasts and birds…"

Mary Wood on the timeless qualities of Justice Douglas' prose.

History & Jurisdiction

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is 800 square miles of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, bisected by the Appalachian Trail.

In the 1800s, settlers of European descent began displacing the Cherokee in this area. President Andrew Jackson's Indian removal policy culminated in the 1838 Trail of Tears, a grueling—forced journey that forced most Cherokee to relocate—on foot—to reservations in Oklahoma and Arkansas. The remaining Cherokee gathered in what became the town of Cherokee, North Carolina, a community that lies at what is now the south entrance to the park. In the early 1930s ownership passed from private hands to those of the nation.

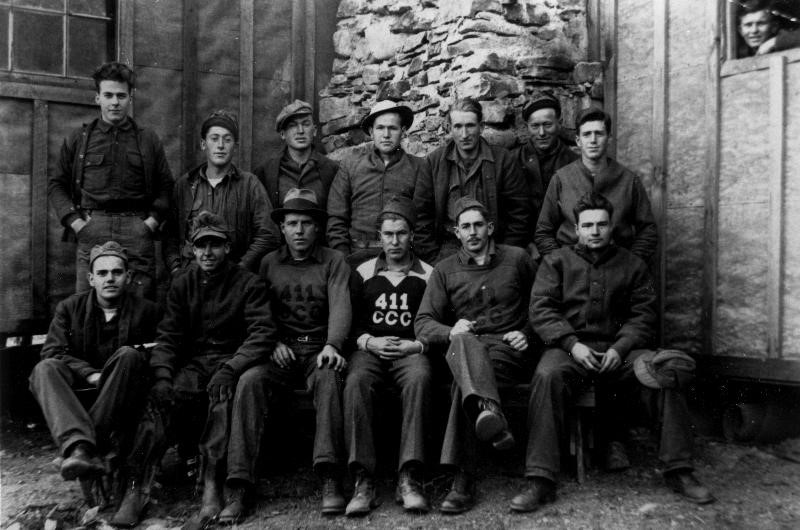

On September 2, 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt dedicated these lands as a new park. The year before, Roosvelt had sent thousands of young men to our mountains’ flanks to build many of our rock walls and arching bridges over our roaring rivers. In Great Smoky Mountains National Park, as many as 4,000 enrollees were assigned to 22 Civilian Conservation Corps camps at various times from 1933-1942, building roads, trails, fire towers, and structures. The legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps, or CCC remains clearly evident today.

The Smoky Mountains are among the oldest mountains on Earth.

The park preserves one of the world's finest examples of deciduous forest and an unrivaled variety of plants and animals. Because it contains so many types of eastern forest vegetation—much of it old growth—the park has been designated an international biosphere reserve. More than 1,600 species of flowering plants bloom in the park, some found only within its borders.

Biologists estimate that roughly 1,500 bears live in the park. This equals a population density of approximately two bears per square mile.

Drawing more than nine million visitors a year, twice the number of any other national park, it is the nation's busiest park.

William O. Douglas on The Smokies

The Smokies offer wonders that never cease. About one hundred and twenty-five species of trees are found there; and more shrubs and vines than that. Each trip is a new adventure. Each season has its own splendor.

Rain or shine, this is a ringside seat, where the hemlock, cove hardwoods, and spruces meet and can be seen at close range…. This is a woodland as it was before man came to value a forest in terms of board feet. This is a forest filled with so many wonders, one man could not ever know them all, even if he saw it every season and examined it from the spores of the fungi of the forest floor to the tops of the wild black cherries. This is a place of sheer wonder, a place of worship. I have not seen woods the world around where beauty is so varied. The Smokies are rich in their offerings. Even the familiar seems different.

The Smokies teach an important lesson to all who love the wildness of the forests and want it preserved. The movement to make this land a park started locally and was actively promoted for five years before outsiders came in to help. In the early thirties the people of North Carolina and Tennessee raised five million dollars to purchase the land necessary for a park. The Rockefeller Foundation then matched the local money, dollar for dollar. Federal money arrived about 1934; but it was only ten per cent of the total. The creation of Great Smokies National Park had its genesis in a local and private movement.

Civilization threatens many of our wilderness areas, even though they are set aside as parks. The pressure for more roads, more lodges, more parking spaces within our national parks is changing their character. Some appear to be in competition with amusement parks. The purpose of the national parks was not only to attract tourists but to further the “outdoor education and exercise” of the people. The Park Service has in the main been faithful to that mandate. Yet at times it succumbs to pressures to turn parks into mass recreational areas. Roads, roads, roads. Resorts, hotels, hostels. These encroach more and more, with Park Service approval. We must stop that trend. We must plan so that mass recreation is outside the parks, not within them.

Democracy should accommodate a great diversity of tastes. There should be bits of wilderness, the edges of which people can reach by car. Roadside picnics fit some needs. Some want comfortable beds at night though they tramp the heights by day. The demands vary. Yet certain it is that we can have no wilderness where wild life flourishes, unless “civilization” is kept out. If “civilization” is brought no closer than the fringe of these wilderness areas, one who can walk only 100 yards may enter the sacred precincts and feel and see the wildness that once possessed America… Of all our national parks, the Smokies is in this respects close to a model. Civilization centers mostly in towns like Gatlinburg, Tennessee. The hollows, streams and ridges of the park are largely unmolested. That should be the aim in all other parks, in all other wilderness areas. Yet as we enter the 1960’s the wilderness of America that is left is more and more shaped and designed for the conveniences of mass recreation. If that trend continues we will become victims of “civilization.” Man will have no chance to escape. Wherever he goes—unless he goes to sea—the crowd will follow him by car.

(My Wilderness: East to Katahdin, 1961)

Impending Threats to Public Ownership

The National Park Service was created in the Organic Act of 1916. The new agency's mission as managers of national parks and monuments was—"....to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations."

Historian Douglas Brinkley talks about Justice Douglas' political advocacy for saving Americas wild places.

History & Jurisdiction

The Brooks Range forms the northernmost drainage divide in North America.

Originating at the Alaskan border with canada's Yukon Territory, it It extends about 600 miles across Alaska from the U.S. border to the Chukchi Sea.

The Prudhoe Bay region has vast reserves of oil. To the west of it is the National Petroleum Reserve of Alaska, which covers some 36,700 square miles. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline crosses the range at Atigun Pass en route from Prudhoe to the Valdez terminal in southern Alaska.

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, encompassing the eastern part of the range, protects one of the world’s most pristine and ecologically diversified high-latitude wilderness areas. It is home to some 200 species of birds, more than 35 different kinds of land mammals—notably polar bears, caribou, musk oxen, wolverines, and wolves—and several species of marine mammals and fish. The preserve also is believed to have substantial petroleum deposits in the North Slope area and has been the subject of controversy between environmentalists and proponents of oil drilling. President Eisenhower set the Arctic Refuge aside in 1960 and to this day, it remains the only national wildlife refuge established “for the purpose of preserving unique wildlife, wilderness, and recreational values.”

President Eisenhower’s original 1960 designation included 8.9 million acres and named the area the Arctic National Wildlife Range. In 1980,Congress and President Carter expanded it to its current 19.6 million acres—an area almost as large as Maine under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, or (ANILCA). Under ANILCA, the range was renamed the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and much of the refuge was designated as wilderness. ANILCA also prohibited oil and gas development on the coastal plain in the northeast corner of the refuge along the Beaufort Sea, but provided the opportunity for a future act of Congress to allow it.

It is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a unit of the National Wildlife Refuge System.

William O. Douglas on the Brooks Range

The Arctic has a strange stillness that no other wilderness knows. It has a loneliness too—a feeling of isolation and remoteness born of vast spaces, the rolling tundra, and the barren domes of limestone mountains. This is a loneliness that is joyous and exhilarating. All the noises of civilization have been left behind; now the music of the wilderness can be heard.

This is the ancient land of the Athabaskan Indians, composed of eight tribes making up the Kutchin nation. Their domain extended over the Brooks Range to the Arctic Ocean. Occasionally they fought the Eskimos. But they were essentially hunters and fisherman who settled on the Yukon and the larger rivers that feed it.

…here in the Sheenjek the wolf is as much a part of the environment as the arctic ground squirrel, the ptarmigan, and the short-billed gulls. This is—and must forever remain—a roadless, primitive area where all the food chains are unbroken, where ancient ecological balance provided by nature is maintained. The wolf helps in that regard. He has, moreover, a charm that is wild and exciting. In this, our last great sanctuary, there should be a place for him. His very being puts life in new dimensions. The sight of a wolf loping across a hillside is as moving as a symphony.

The vast, open spaces of the arctic are special risks to grizzlies, moose, caribou, and wolves. Men with field glasses and high-powered rifles, hunting from planes, can well-nigh wipe them out. In this land of tundra, big game has few places to hide. That is another reason why this last American living wilderness must remain sacrosanct. This is a place for man turned scientist and explorer, poet and artist. Here he can experience a new reference for life that is outside his own and yet a vital and joyous part of it.

(My Wilderness: The Pacific West, 1960.)

James M. O'Fallon is the editor of Natures Justice, an anthology of William O. Douglas' writing .

Impending Threats to Public Ownership

The Alaska House has introduced an all-out land transfer bill, stating that the (1) US shall ”relinquish title to public land or an interest in land in the state; and (2) transfer title to public land or an interest in land to the state.” before 2017. The bill is currently in committee. Read more... http://www.protectourpublicland.org/alaska/

STUDY GUIDE QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES

Which agencies manage public lands and parks? How many are there ?

Why does federal land management wishing to preserve land for wildlife or recreational use sometimes come into conflict with special interests?

Consider the public lands that you have visited or have experienced in other ways (readings, films, etc.). Find out the current status of at least one of these places and assess how any proposed changes might impact your experiences and those of future generations.

Contrast the financial realities of federal management of public lands with the budgetary implications to individual states, if the status of public lands were to be transferred.

What role does the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) have in the campaign to transfer public lands to individual states?

Extend your research to locate any bills in the state legislature where you live that are under consideration to transfer ownership of public lands. Predict what effect the passage of such a bill would have on the public.

What elected official sponsored each of the bills below and what is the current status of those bills in the United States Congress?

H.R. 3650 would allow any state to claim ownership of up to 2 million acres of a National Forest (roughly the size of Yellowstone National Park), on the condition that the state then prioritize logging over other uses of the land.

H.R. 2316 would allow states to take possession of 900,000 acres or more of National Forests and hand control over to small groups representing special interests, appointed by the state’s governor.

H.R. 4579 would undercut potential wilderness designations and careful land management by handing over travel management decisions of public lands in Utah, owned by all Americans, to a small group of counties.

Contact your congressman, congresswoman or senator asking them about their positions on public lands or share your views with them.

Get started by finding out who your senator and congressperson is and get their email.

Hike, paddle or otherwise enjoy you own nearby wild space of wilderness. This could be a trip you have already made. Document your experience with writing and visual work - drawings,photos, video,etc - describing how what you did helped you, as Douglas said, "maintain your freedom by allowing your idiosyncrasies to flower."